Bruce Kasanoff recently posted an interesting article titled “Why Good Is Not The Enemy Of Great”. (https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-good-enemy-great-bruce-kasanoff). In his article he makes a provocative statement:

“Our mindless obsession with greatness may well be the root cause of much that is wrong today in the world of business and, well, the world.”

Do not miss the key word in that statement – “mindless”. While Kasanoff’s point is important (just as Collin’s emphasis on greatness is), it does not provide appropriate guidance for leaders to manage the issue. Unless “mindless obsession” is defined and addressed, it will not be possible to achieve the appropriate relationship between good and great.

The urge to create a high achieving organization has led many leaders to initiate an all-out assault on creating greatness. A lack of misunderstanding about how high achieving organizations must be both good and great has often resulted in organization misalignment that could have been prevented and it has prevented leaders from achieving their primary goal: creating high achieving organizations.

Issues Contributing to the Problem

During my work with various organizations, I have observed three practices that shaped my thinking in this area.

First, many organizations struggle with the need for part of their organizations to be innovative and focused on excellence while other parts of the organization are simultaneously required to be extremely cost conscious and focused on “good enough”.

Second, many organizations “over-engineer” products or services. Too many “bells, whistles and features” are created for what the customer wants, needs and is willing to pay for. Over-engineering occurs because a design is possible, the challenge is exciting and the work is intriguing to the designers. People want to be proud of their work; every part of the organization wants to be world class and design and implement the best techniques possible so “Cadillac” approaches are applauded over a “Volkswagen” effort (Is that analogy still appropriate?)

Third, for many organizations excellence is primarily defined as growth in direct reports, organizational levels, positions and customized services. More is confused with great. As a result, increased size is good (and rewarded, both organizationally and individually). This is especially true for government and not for profits where profit does not require overhead to be kept in check.

These issues combine to present an interesting challenge. Should and can an organization be both good and great simultaneously? If that is appropriate, how is it created and maintained? Answering these questions is important for every organization.

An Issue Of Leadership Direction

The problem of misplaced or unclear emphasis rests with leadership. When leaders allow subordinate managers the latitude to innovate without guidance, direction or priorities, greatness in one part of the organization may be achieved to the detriment of the entire organization. Many times leaders do not confront this issue because they are afraid they will “de-motivate” highly motivated staff or indicate to them that their part of the organization is not as high as important as others. Telling a staff member good is what is desired is seen as de-motivational. The insidious part of this failure to clarify what is truly needed and desired is that the search for greatness runs rampant and the entire organization becomes more complex and highly frustrated.

Interestingly enough, the search for greatness is often higher in staff functions than in line operations. But uncontrolled innovation for greatness in these areas can result in increased complexity and work for the rest of the organization. Time and focus are diverted from making or improving products and services to implementing a staff initiative or complying with a new system or program. As a result, an uncontrolled emphasis on greatness in staff functions can actually have a double negative impact on productivity:

1. It takes away resources from areas where greatness is a high priority and resources are needed.

2. It adds additional work onto line operations thereby minimizing their focus on productivity.

For example, in one organization the Human Resource Department desired to be world class and wanted to create an “employer of choice” culture. HR innovation abounded. For the organization, however, human resources innovation was far down the line the list of priorities. (In fact what was really wanted was simple, fast, non-time-consuming and cost effective HR services). There was not enough money for both desired product and service innovation and the staff innovation that was proposed. In this case, the Human Resources department was a place where senior leadership felt “good” was good enough. That expectation was never communicated to the HR function. This particular organization could never align its focus between good and great and as a result, it became more complex, slower and bureaucratic.

High Achieving Organizations Must Be Both Good And Great Simultaneously

The other side of this equation occurs when greatness is required but not demanded. If great is needed and good is produced, the organization will never achieve its potential. Many organizations live is this state, tweaking (not innovating) around the “edges of the current state” rather than searching for greatness. Eventually this type of organization loses its capability to distinguish between good and great. As a result, it comes to believe it is better than it really is (a problem that every consultant has observed).

Therein lies the conundrum between the views expressed by Jim Collins and Bruce Kasanoff. All organizations must be both great and good simultaneously (but in “all the right places”).

Leadership Implications

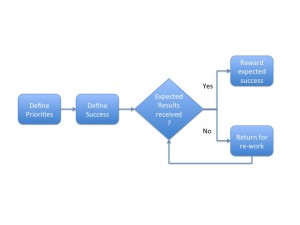

So what can a leader do? Leadership can show its greatness by performing with precision three very important tasks that insure a proper alignment between good and great. While the diagram below is simple and intuitive, it is the precision and rigor with which it is executed, that makes the difference between high achieving and mediocre.

1. Clarify priorities based on vision and mission.

• Lead by clearly distinguishing between areas where excellence is required and where “good” is “good enough”. Organizations cannot be “world class” in every area.

• Leaders need to be clear about where excellence is required and where it is not. (Confusing these two areas paves the way to everything being a top priority that means nothing is a top priority). Ultimately this results in organizational complexity and mediocrity.

• Priorities must be clearly communicated and understood throughout the leadership and management structure.

• De-democratize the budgeting process. Stop the practice of giving every unit an increase every year. For some parts of the organizations staying level, or even getting smaller, is the right option.

2. Define What Success Looks Like.

• Lead by clarifying the criteria on which an excellence or good will be evaluated (Define what success looks like for both great and good results so all staff have clear targets).

• By clarifying the criteria for the outcome instead of the specific alternative, leaders can develop a positive method to engage and challenge employees.

• There will be multiple ways to achieve desired results that individuals or groups can explore. Turn this analysis and decision over to employees to build ownership and commitment.

3. Reward Appropriately.

If work is required to be good, not great, and if that level of work is produced, it should be rewarded just as if great work was expected and achieved. But if excellence is created in an area where good, not great, is needed, it should not be rewarded but should be re-worked to meet the defined expectations.

Good is a barrier to great where greatness and excellence is needed. But great can be a significant barrier to operational excellence when the quest for greatness has no direction or guidance.

Copyright 2015 9 By 9 Solutions All Rights Reserved

Dear Doug,

When I have visited a company, I saw that a senior manager decided to create excellence in documentation and process.

He established a team and they had a lot of meetings and finally they prepared a manual that had more than 50 pages. It was very complex and not practical. People didn’t understand and problems or issues continued. I thought that it could be simple, practical and understandable for the people. They tried to create excellence and it was a barrier to good.

This post has a lot of great and valuable lessons.

Thank you for your excellence.