Situational ethics have taken over our collective philosophy. Our beliefs and values have become preferences instead of convictions. If there is greater good to be gained by violating principles and values then one should abandon their values and take the expedient route. In certain situations little white lies are acceptable (even desirable) and promises should sometimes be considered as dreams not commitments. Principles and values are now used to build a façade of character that will be practiced as long as it costs the person (or organization) nothing to believe in them. The situation (and what can be gained), not values, is the criterion used to determine what is right or wrong. As a result, trust and integrity have taken a huge hit and leaders that have chosen the situational ethics route are universally distrusted. These leaders verbalize all the right words, beliefs and platitudes but when they justify compromising those beliefs because the situation dictates it, people realize there was no conviction behind those beliefs in the first place. Empty words like “People are our most important resource” “We could not have done it without them!” cause employees to cringe when they watch the leader’s behavior act in opposite fashion. As a result employees, followers and yes even citizens stand by and watch with disgust how actions do not live up to the words they hear articulated.

Ethics and Trust

In a University of California, San Diego laboratory experiment to test people’s willingness to lie to a partner in a game, 14% of people always chose to be truthful, even if lying would have benefited them, and 14% chose to lie whenever they stood to gain, according to a team. The rest reacted in variable ways to incentives, sometimes lying and sometimes not (situational ethics), except for one participant who always lied, regardless of circumstances.

According to Ernest and Young “20% of almost 3,500 staff quizzed in 36 countries in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and India said they had seen financial manipulation in their companies in the last 12 month. In addition 42 % of board directors and top managers surveyed said they were aware of some type of irregular financial reporting”. (Earnest and Young 2014 Fraud Report).

In The Fall of Business Ethics: A Mark against Society Today by Leanne Hoagland-Smith, she writes “Unfortunately, many young people in the process of their education from high school to post-graduate degrees appear to have embraced a convoluted definition of cheating. Most older business professionals will agree that cheating is unethical. Nationally, it is estimated that 75 % of all students cheat at the high school level. Then examining the rationalization for this unethical behavior at the college level is best summed up by this anonymous student: “There’s so much pressure to get a good job, and to get a good job you have to get into a good school, and to get into a good school, you have to get good grades, and to get good grades you have to cheat.”

Carol Kinsey Goman reported in a survey of more than 500 employees that 67% said their senior leaders lied to them and 53% said their direct supervisors lied. (I guess integrity is not one of the most important characteristics of a leaders as we read in many posts.)

According to a 2013 AP-GfK poll Americans have trouble trusting each other in everyday encounters. Only 33% of Americans say people can be trusted – down from 50% in 1972. In 2013, 66% indicate that “you can’t be too careful” in dealing with others.

Author Robert C. Cialdini found that cheating at the top of organizations generates huge hidden costs, even if leaders think they’re “getting away with it.” Cialdini reported that “teams whose leaders cheated scored 20 % lower than teams whose leaders remained honest. In other words, when leaders cheat, they make employees less productive. (Lack of conviction is contagious across groups of people)

The American Psychological Association reported that 24% of employees do not trust their employers (2014 Work and Well Being Survey).

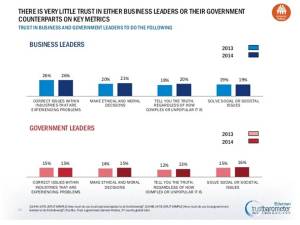

US News and World Report reported that faith in leadership had declined and the Edelman Trust Barometer indicated in its 2014 report that business and government leaders are viewed as untrustworthy:

The bottom line is that most leaders’ ethical beliefs are preferences, not convictions and, as a result, trust declines as their behavior is inconsistent with their words.

Guidance From An Unusual Source

Valuable lessons about ethical convictions can be learned from the U.S. Supreme Court Case, Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972). In this case, several Amish parents including Jonas Yoder believed that the state public school system was teaching a false religion, secular humanism. In their minds God had been removed as the center of all truth and had been replaced by man as the ultimate authority. To these parents secular humanism was idolatry of the highest form and they refused to send their children to public school, choosing to home school them instead. Unfortunately for the parents, the state of Wisconsin disagreed with their assessment of the state school system and ordered them to place their children in public school as required by state law. When the parents refused the state of Wisconsin’s order, the state told them that the state would place them in jail for refusing to comply with a state law. When the parents again refused to comply, the state of Wisconsin told them they intended to take away their children from them and place them in foster care where they would surely attend public school. Again the parents refused and finally the state offered a compromise. The parents could place their children in the public school system and then they could file suit against the state. That way the parents would not be jailed or lose their children and if they won, they could remove their children from the public school system for good. Again the parents refused and the state of Wisconsin filed suit against them for their refusal to comply with state law requiring their children to attend public schools. The state of Wisconsin filed suit in state court and after deliberation the jury found for the state. The parents appealed their case to the state appeals court where once again the verdict was for the state. The case was appealed to the state supreme court where the parents won but the state appealed the case to the U. S. Supreme Court which agreed to hear the case.

After hearing the case, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously found in favor of the parents.

Lessons To Be Learned On The Importance of Convictions

What lessons can we learn about values and ethics from this U.S.Supreme Court case?

1. Beliefs (and ethics) are founded on convictions not preferences. The Constitution protects a person’s religious beliefs but it only protects if the beliefs are convictions, not preferences.

2. Convictions are recognized by their consistent practice. But how can one tell the difference between conviction and preference? The Supreme Court indicated that a conviction is a belief that a person holds to even when it costs them something to maintain that belief. If Jonas Yoder and the other parents had succumbed to the state of Wisconsin’s threats – put their kids in school or you will be jailed or the state will take away your children from you, or if the parents had accepted the state’s compromise – put your kids in public school and then file suit against the state, they would have proven they preferred their beliefs but did not really hold those convictions. As a result of their holding steadfast to their values against all threats and even compromise, the parents demonstrated their convictions were real.

3. Convictions can sometimes be costly. It would have been convenient for the parents to accept the state’s compromise. They could have kept their children out of foster homes and maybe won their case. But giving in to compromise would have proven they did not really believe what they espoused. If fear of loss or disadvantage keeps people from practicing their beliefs, then they are demonstrating they do not believe those values, they only prefer them.

How can leaders build trust?

There are three requirements that are necessary for trust to exist.

The first requirement is that a person has a settled belief in something of value and importance. Unfortunately this is not as easy as it once was. Our homes, schools and churches have failed to teach and practice absolute ethical values and principles and that void of ethical development is becoming more and more noticeable in behavior and decisions. As a result, beliefs have become individual preferences and how to apply that preference is solely situational. “I will be honest with you as long as it is convenient”, “I will not lie to you unless it is required” is the new norm. Situational ethics have caused us to lose both our definition of right and wrong and our ability to distinguish between them.

Second trust requires that leaders not only have strong core beliefs but also that those leaders are committed to practice those beliefs no matter the personal or organizational cost. We look for leaders with convictions, not just preferences (and yet when they stand up for what they believe, we criticize them). We yearn to see values that are consistently practiced even if it costs the person something to do so. We look for leaders for whom it is more important to be true to what they believe than to find the expedient way out.

The third requirement is that beliefs must be transparent. If values and convictions are hidden, it is almost impossible for those invisible beliefs to build long-lasting trust. Transparency means the belief is obvious to those around them. Unfortunately, transparency is also on the decline partially due to political correctness (don’t want to offend anybody with your values) and partially due to the fact that the teaching of absolute values have been taken out of schools, churches and even most homes. We should not therefore be surprised that ethical waffling is practiced in the workplace and that trust is at an all-time low. We should also not expect to see immediate change in the area of trustworthiness.

Today, like Diogenes, we search in vain for people, leaders, of integrity and instead we find situational ethics. We look for people we can believe in and find empty words that are quickly discarded when the cost or risk is too high. If leaders are to build trust, they must rebel against the situational ethics mentality of the day and begin to define what they truly honor, value and believe in. Unless a leader has a clear personal leadership philosophy that he or she can refer to for guidance when things are difficult, their inconsistent behavior will only be seen as self-serving. Until leaders can clearly answer the question for themselves, “what do I honor, value and believe in?” and then consistently live those values out in front of others, he or she should never expect to earn another’s trust.

Unfortunately the waffling confusion of situational ethics is teaching many it is better to be clever in figuring out how to get around one’s espoused values and beliefs than to consistently practice them. So as situation ethics remains the standard, not the exception, leadership trust will continue to decline.

Leadership Implications

1. Determine what you honor, value and believe in. Take time to list the ethical values that both you and others expect from yourself. (Note: this will and should take time).

2. Test those beliefs by asking yourself if there are any circumstances under which you would not practice that belief. If so, remove that ethical belief off your list.

3. Think through the implications of your beliefs. Ask yourself, “If I truly honor, value and believe these items, what behaviors should my employees, staff, peers and friends (and family) except from me.” If you cannot live up to these expectations, take the belief off the list.

4. Assess the remaining list to see if this is the type of person (leader) you truly want to be and would be proud of being. If not, start over with step 1.

5. Be prepared to communicate your beliefs through your leadership philosophy with your staff and peers.

6. When faced with a difficult situation, ask yourself, “If I truly believe these values, what should I do in this situation?”

Copyright 9 By 9 Solutions 2014 All Rights Reserved